BOOK REVIEWS

Pierre Boulle’s Planet of the Men

19 August 2025

“But in the unproduced Boulle script, the questions are again raised about what power supports our notion of civilization, and Boulle links the cognitive and physical, the technological and the linguistic.“

Not many realized that Pierre Boulle, author of the original novel Planet of the Apes in 1963, who saw his novel turned into a film with Charlton Heston and Roddy McDowell in 1968, would try to take the career further by writing a screenplay sequel to that old film. Following Planet of the Apes would be Planet of the Men. It was submitted to 20th Century Fox as a full script but–for reasons I do not know–was rejected. But the raw version of it is circulating around the internet, and I found a copy. As an Apes fan since the original five films, I had long ago read Boulle’s original novel–quite different from the film versions. And, as someone who even while young recognized the often gimmicky and tawdry apes IP afterwards: from the comic books, 1970s live-action and cartoon TV series, and 1990s video games to the later reboot series and the newer Kingdom series.

There are those who would make a unified canonCanon means "center," and a literary canon is a set of works... More of the disparate storylines, but this is hardly necessary. Equally, the technology/social development misalignments trouble the more casual or literalist readers and views: in Boulle’s original novel, for instance, the apes are technologically more advanced, drive jeeps, etc. Our original astronauts, too, don’t travel to a “future earth” at all but to a planet near Betelgeuse. What is more important, perhaps, is our consideration of the themes which emerge from each; and, of course, what Boulle himself desired. Does his sequel script match more the 1968 film’s philosophy or the novel’s? And how does it compare to what the studio finally went with, the much reviled Beneath the Planet of the Apes in 1970?

To be sure, the overall ironies and the socio-political commentary of Boulle and the films largely overlap. What is the dividing line between beast and humanity? How do our educational and political institutions foster a narrative of superiority which is invalid? Can any beast ever escape its bestial violence? More specifically, too, both novel and films satirize specific cultural moments and behaviors.

But there is a lightness in Boulle’s original Apes that reminds us over and over that it is literary fantasy, despite its grim violence. The non-sensical ending—one that the Tim Burton/Mark Wahlberg 2001 film partly imitates—and an additional frame of a space message in a bottle, all remind us that this is fantasy, allegory, not anything to form logical plot-level coherence. And, after all, how could we miss that? It’s friggin’ ape-human reversals over and over. There is little to any Apes creation that is subtle.

But while the 1963 novel and the 1968 film differ in particulars and character names, while the film slims down the events of the already slim novel, they both focus on the same questions of theme: who are we, really? By the different ends of both versions—Boulle’s space-faring apes reject the story in the bottle as ludicrous fantasy for no human could ever write anything; Fox’s human Taylor famously finds the fallen Statue of Liberty and discovers that he has never left Earth—we see a similar final commentary: the primary apex-predator position held by human civilization is frightfully precarious, both held in place and threatened by our bestial violence.

Now, in Planet of the Men (1969), Boulle continues this theme, doubling down on this reversal and underscoring that propensity to violence. Like the more fantastic elements of the novel, he cares little enough for the logic of science and history, only wistfully clinging to social development and devolution to make his point. But, significantly, while the only political commentary Beneath the Planet of the Apes can make is of a subterranean human enclave which literally worships the Omega bomb that will end the world, Boulle’s script packs in a far more compelling vision, though one which requires, at last, no further sequels.

Boulle’s script begins at the end of the 1968 film, Taylor/Heston on the beach with Nova. He is soon confronted by a tribe of inarticulate humans who first threaten, then fear, and finally revere him as “the speaking one.” Taylor resolves to raise these stone age humans up to become a great civilization. Meanwhile, the lead ape Zaius is determined to hold on to power and falls into a paranoia about Taylor; he decides finally to raise an army to eradicate the human threat once and for all.

All of this takes place over nearly two decades of time. In that time, Taylor and Nova have a son who is remarkably bright. He teaches many humans to speak again, to learn, and ritually offers them control of fire. Once learned, all means of production become possible. He discovers one who spontaneously produces cave art; Taylor yells to the sky: “We have arrived!” Not a few pages later, this creative artist will invent a crude grenade from the rifle shells taken after gorilla raids. First primitive huts are built, to be followed by Babylon-level cities. It isn’t until Cornelius and Zira arrive with warnings about the coming army that Taylor turns his human production to war.

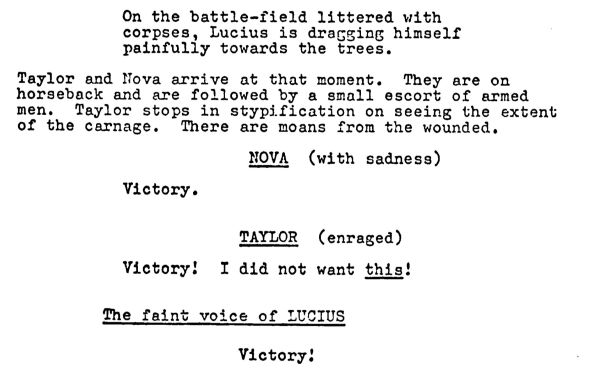

As we might predict, the ape army significantly underestimates Taylor’s work, and in a great battle, it is overwhelmed by the human defenders. Taylor’s troops capture prisoners of war; but his son, caught up in revenge and bloodlust, together with his young friends unschooled in military history or a long-term vision of human-ape peace, decide to march on Ape City and destroy all of it. Taylor arrives too late to stop them, and the slaughter of civilian apes and children is near complete. Taylor is imprisoned when he protests, his founding of the new “civilized” humans forgotten.

Intriguingly, in fear and despair, the ape survivors return quickly to their animal selves, forgetting how to think and talk. They begin to run again on all fours within minutes of their defeat. Cornelius and Zira, in the prison with “primitive apes,” feel themselves losing their cognitive abilities, and so commit suicide rather than become animals. Taylor is shot dead in a scuffle, and all that remain are aligned with the human victors. Boulle adds a final scene that finds Zaius and his counselors as clownish circus performers in a human-run circus.

It is a bleak ending, absurd in its narrative of the speed of cognitive and civilizational rise and fall, but what of that? Instead I wonder at why the Boulle script feels far more bleak than either the first novel or the second film. While the Fox writers could imaginatively muster nothing more creative and despairing than a doomsday bomb which would literally vaporize Earth (some say that they did it to prevent more sequels from being produced, which would only add to the failures), we can’t help at one level to see that film ending as more a mercy killing. The film’s ironic attitude is thin (which it will recover again only slightly in the third and fourth films; let’s not speak of the fifth, Battle for the Planet of the Apes). The apes are cardboard characters and violent; the “advanced” psychic humans are cardboard and violent; the past-Earth astronauts have no serious roles to play except to push the endtimes button on the whole business. (Even the book treatment by Michael Avallone could do little more with the script than add a strange cross-species sexual fetish mid-battle.)

But in the unproduced Boulle script, the questions are again raised about what power supports our notion of civilization, and Boulle links the cognitive and physical, the technological and the linguistic. How thin the lines between beauty and violence in our imagination! How fragile our utopic visions (no matter how conceived–primacy through genocide for Zaius, peace for Taylor) when they meet the reality of weaker thinkers and incompetent leaders! And how easily it all falls away, its history and lessons lost, in a moment of fear or with a single bullet. The tragedy in Boulle’s final circus scene is not only the gross parody performed by the orangutans; it is that the human spectators fail to see that they are the objects of that ironyA "deflection of expectation," where words, situation, or pe... More.

Boulle’s script is far from a superior work, hindered as it is by the requirements of a screenplay built upon the Fox plot. It is weaker still in its extraordinary effort to make a dreamer of Taylor or to effect so grand a subject as the rise and fall of humanity in 90 minutes of science fiction. But for all that, Boulle is a good writer (he won an Academy award for the screenplay of his own novel The Bridge on the River Kwai). And while I would not advocate a production of the script now, or that the history of the Apes franchise been altered by its production then, for fans of science fiction and for the series in particular, it’s a script worthy of its own “alt” publication rather than its current quiet web circulation.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Recent Comments